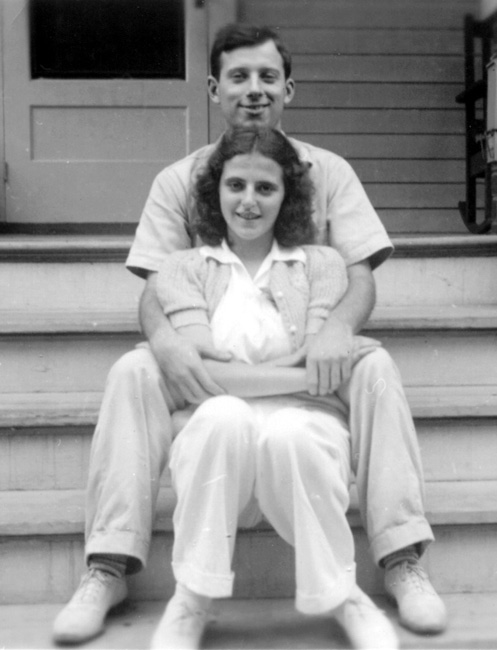

Lore and Don just before moving to Talladega in 1942.

Lore and Don just before moving to Talladega in 1942.

Don and I had met in a sociology classroom, he as the teacher and I as his student. During the first two years of our marriage at the University of Illinois, we became increasingly interested in race relations. It seemed natural for us to accept an offer to join the racially mixed faculty of Talladega College in Alabama. Established for Freedmen after the Civil War, Talladega was exempted from the state segregation laws by a state charter.

On the day before Thanksgiving in 1942, Don and I left the Talladega College campus for the first time since the semester had begun. Our six-month-old Peter was in the capable hands of Arvada Lacefield, a student who lived in our home, and our car was crowded with students hitching rides in order to spend the holiday with relatives in Birmingham. Our main mission was to buy Thanksgiving turkeys and much needed clothes with our first paychecks.

Although Birmingham was only sixty miles away from Talladega, it proved to be located in a world far distant from the integrated campus.

After our arrival in Birmingham, the students borrowed our car while we shopped, and Kenneth Pangborn was designated to return it by dark.

We completed our errands in the afternoon and found ourselves with idle time. So decided to visit an acquaintance whose office was only a short distance away in the Masonic Temple Building. Louis Burnham was director of the Southern Negro Youth Congress. He was a brilliant recent graduate of New York’s City College. Since we were all hungry, we decided to go out to eat while we talked. All three of us were new to the South, but we knew that Louis would not be served in a white restaurant. We therefore asked a prominent black physician where we might dine. He recommended Nancy’s Cafe, where he himself had recently eaten with our white college president.

Halfway through our fried chicken dinner, two policemen with drawn clubs arrived at our side.

“Are you Nigras?” they shouted at Don and me.

“No,” we answered, “can’t you see, we are white.”

“You’re all arrested, follow us!”

With smirks on their faces, they escorted us to a waiting squad car and drove us to the police headquarters, sending the radio message, “We’re bringing them in!” This all happened so fast that I was completely numb from shock.

At the police station we were asked to give, among other information, our places of birth. Then we were escorted to a patrol wagon. One of the officers gestured to the open back door and said, “Gentleman, get in.”

Since Louis was closest to the door, he started to climb in. The officer quickly and forcefully grabbed him by the collar of his coat and threw him to the ground while shouting, “You’re not a gentleman. You’re a boy! And don’t you ever forget it!” Then he waived Don in and closed the door after him. Don found himself in the company of a fellow gentleman—an unkempt drunken white.

Next the policeman driver removed a back panel from the cab of the wagon, motioned Louis into a dark compartment the shape of a body, replaced the panel, and made me sit in front of it, next to the driver. Bull Connor’s Birmingham police did things right—they even segregated patrol wagons according to race and gender!

We were on our way to the Birmingham jail, which was a long way from the city center. My body felt clammy and cold; my heart beat quickly. How did I know that we weren’t on our way to be beaten and dumped? Would I ever see my baby again? I cried silently.

I was relieved when I noticed neon signs advertising bail bondsmen—relieved to be arriving at the jail! There was no opportunity to communicate with Don after this. I was given over to a jailer who emptied my pocketbook of its contents for “safekeeping.” Then I followed him in my new green wool suit and my new wide-brimmed tan felt hat to the second floor and the cell for white women.

On the way we passed several freestanding wooden cages that held black women in solitary confinement. My male escort greeted each woman with some obscene remark and was answered by curses and bar rattling, which he answered with threats of beatings.

When we reached my cell, the jailer called for Alice, a hefty, sallow complected woman, wrapped in a robe, whose head was crowned by pink curlers. Alice apparently was the inmate boss.

“I brought you a new girl. Show her the ropes.”

With that he unlocked the cell door, pushed me in, and locked it up again.

Alice walked over to me, sniffing.

“Sober! How did you get in here? I’ve been here a year and a day, and you’re the first sober one to come into this joint. What did they pick you up for?”

“My husband and I were arrested for eating in a Negro restaurant.”

“What? You heard her, girls! She ate with niggers! Her husband was with her! Can you believe there are the likes of her? Put in jail with her husband! It can’t be true!”

The six other women glared at me in disbelief. That was the last any of them showed interest in me. They moved away from me on the bench where we were all sitting. To them, my crime against their mores was far more serious than their prostitution and loitering.

I had become an outcast in the Birmingham jail.

Our quarters were dingy, and the stench of urine came from the overflowing toilet. Several unpainted benches and a bare table were the only furnishings. An adjacent room was filled with cots with dirty mattresses and blankets. Cockroaches, two inches long, scurried across the littered floor. A bare bulb lit their path.

While the other inmates entertained one another with sexually explicit anecdotes and tales bragging of their exploits, I sat alone wondering what would happen to me next. My heart was pounding loudly and rapidly.

At nine o’clock the jailer returned to turn off the lights. He shouted to Alice, “Show the new girl her bed and a nail where she can hang her things.” She complied, but I wouldn’t part with my new jacket and hat.

“She doesn’t trust us with her stuff!” they guffawed. “Things are safe in jail, honey!” More laughter.

I lay down in all my finery. I tried to think of little Peter, but I could only feel sorry for poor Lore, father’s little girl, in jail.

Some hours later the jailer reappeared to take me downstairs for interrogation. The police had noticed that I was born in Germany. America was at war with the Germans. I ate with Negroes in Birmingham, Alabama. They reasoned that I must be a German spy sent by Hitler to foment unrest among the Negroes. They thought they had stumbled on a big plot.

The special police detail on Un-American Activities was called in to investigate. When they discovered, however, that I was a Jewish refugee who had fled from Nazi persecution, they suddenly became very compassionate.

“Our boys are over there to take care of those beasts. You have nothing to worry about. Aren’t you glad you’re in America where we have freedom and democracy?”

Now, with their spy catching over and their patriotic sentiments voiced, they revealed a third set of priorities—their need to protect white womanhood.

One said to the other, “That’s a sweet little girl. She’s all right. She’s just too much in love with that scoundrel of a husband of hers. He got her in all this trouble. Let’s call him in.”

“No!” I protested, “I do my own thinking. I have a mind of my own, and I use it.” They only responded with condescending smiles.

So Don was brought in. His erect gait and confident expression were in sharp contrast to his rumpled suit and disheveled hair. They made him sit in a chair, one policeman with a drawn club in front of him and another behind him.

“Spill it! What are you trying to do coming here and breaking the law?”

“I didn’t know that I was breaking a law. I wanted to eat with a friend and only knew you had strong desires to keep the races apart.”

“Where did you pick up your crazy ideas?”

“I suppose I learned them in my seven years at the university!”

“What do you teach at that nigger school?”

“I teach sociology.”

“That’s that social equality stuff,” one commented to the other. “Would you marry a nigger?”

“I’m already married and you wouldn’t want me to commit bigamy,” Don answered in his reasonable and quiet voice.

“Would you have married her if she had been one?”

“That question doesn’t make any sense to me as a sociologist. The fact was, she wasn’t.”

“Do you have any children/”

“I have a little son.”

“Would you let your son marry a nigger?”

“I believe marriage is a private affair and I would let him marry anyone he loved, but I surely would warn him about the difficulties he would meet from people like you.”

“Oh, no you wouldn’t! Every white man would rather kill his son before he would let it come to that!”

Just then a red-haired prostitute was brought in, and an officer pointed at us and asked her, “Would you like to be educated like them and love niggers, or would you rather be ignorant and hate them?” Before she could answer, he thumped himself on the chest and continued proudly, “I’d rather be ignorant.”

The officer turned back to us.

“Who’s taking care of your baby right now?”

“A student lives with us, and he is with her.”

“Does she eat in the kitchen?”

“No, she eats with us in the dining room.”

“You nigger lovers! Young lady, I’m warning you that you better get some sense into that husband of yours or some night you’ll find him hanging from a tree. All we got to do is tell our friends in Talladega about you, and he won’t get a second chance.”

They then ignored us and discussed whether to send me home to be with my baby and double Don’s bail instead.

A clerk entered and announced that Mr. Rasmussen’s chauffeur had arrived to get instructions as to what he should do about the car. Don was sent to speak with him. Kenneth Pangborn had traced our whereabouts and had sized up our situation well enough to pose as our chauffeur.

Don returned to the interrogation room with the brilliant idea of letting our chauffeur drive me home to Talladega.

“Is he white?”

“No.”

“You son of a bitch! You would let a nigger drive your pretty little wife in the dark of the night to Talladega and have him rape her on the way! If you won’t protect her, we will. She’ll spend the night here with us where she is safe.”

We were sent back to our cells.

About three o’clock in the morning I was ordered out of the cell with all my belongings. Someone had posted bail for us.

Days later we learned that Louis Burnham’s co-worker in the Southern Negro Youth Congress, James Jackson, had overheard every word of our interrogation while he was waiting to get Louis freed. His report on our behavior under duress won us many new friends in the black community.

It was also through Mr. Jackson that we learned how the elderly black physician who had recommended Nancy’s Cafe had come to the jail and secured our bail. With hat in hand and feet shuffling, he engaged in the ritual prescribed for interracial interchange, using plenty of “Yes sirs” and “No sirs,” which were rewarded by a benevolent pat on the back and praise for “knowing his place.” Had we known the price of our freedom, we would have remained in jail.

The news of our arrest reached Talladega before our own return. The president greeted us warmly and assured us that we had upheld the best traditions of the college by our conduct. As its leader, he would immediately obtain legal counsel for us so that we would be represented in the forthcoming court hearing.

No white Alabama lawyer could be found who would take our case. All of them considered defending us to be professional suicide. Using northern lawyers was considered out of the question, because it would increase racial tension. Louis Burnham would be represented by Birmingham’s only black lawyer, a Talladega trustee. The only help given us by the most liberal local legal firm was getting the court calendar rearranged so that our case would appear last on the day’s docket. This would reduce the probability of racial violence, because the courtroom would have emptied out by then.

Thus we went to court without counsel and with only our tall Lincolnesque character witness, our college president, at our side. The charges brought against us were disorderly conduct (specifically, incitement to riot) and operating a restaurant where the races were not separated by a seven-foot wall beginning at the floor.

The police related the circumstances surrounding our arrest. Don described the events that brought us to Nancy’s Cafe. The judge probed for details that would indicate a conspiracy. In his answers to the judge, Don repeatedly referred to Louis as “Mr. Burnham.” Unknown to Don, who was standing facing the judge, this created such raising of clenched fists and low-voiced threats among some courtroom observers that I wondered whether we would later be assaulted on the street.

After hearing all the evidence, the judge reluctantly decided to interpret our behavior as not having been deliberately unlawful. He then proceeded to lecture us on democracy. “If we in the South make it illegal for a colored to eat in a white restaurant and let a white eat in a colored restaurant, then we are discriminating. If we make it illegal for a white to eat in a colored restaurant and let a colored eat in a white restaurant, then we are discriminating. But if we make it illegal both ways, then we have equality.”

The judgment for each party involved was a fine of twenty-five dollars or ten days in jail.

We seriously considered returning to jail and becoming a test case to challenge the ordinance under which we were arrested. Roger Baldwin, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union, thought it was an ideal case to take to the federal courts. We discussed this with several college authorities and with Louis Burnham, but they all thought this action was not advisable at the time. There were already dangerous Klan activities in Talladega. Our president had just succeeded in getting local hearings begun by the Fair Employment Practices Committee to investigate the refusal of Alabama defense contractors to hire black women in a local defense factory, and robed Klansmen had fired shots into campus homes in retaliation.

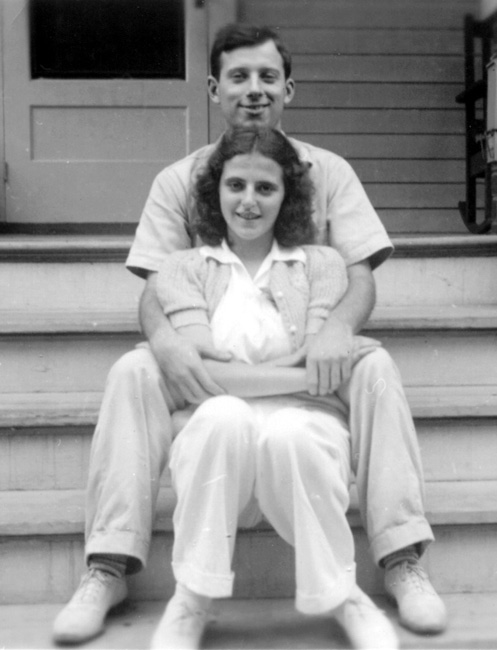

Our case made headlines in the black press, and offers to pay for our fines came from all over the country—even from black soldiers in the front lines of the war. I still possess a copy of The East Tennessee News of December 3, 1942, with the large front-page headline, “White Tutor, Wife Fined For Eating In Colored Cafe.”

Go west and up the hill on Battle Street from Talladega’s courthouse square. Pass Strickland’s Funeral Parlor until you reach De Forest Chapel. There turn left and go past our house and a few other well groomed college buildings. Keep going along the narrow macadam road past neglected fields and unkempt open spaces. Then cross the Sylacauga Highway, jump over the railroad tracks, and, if you don’t get stuck in the mud holes, you will arrive at Furnace Quarters.

It was early in 1943, and daily I watched tired women dragging themselves along this road with heavy bundles slung across their backs as they returned to Furnace Quarters after long hours working in the fields or the homes of white mill workers. They had kindly greetings for me and our nine-month-old Peter, who was usually playing on our lawn. Cooing and babbling, he would extend his chubby arms in a joyful gesture of greeting to the unexpected passersby.

They would often pause to admire our healthy active baby, sit on our steps, set their burdens down, and chat while resting their swollen feet. Invariably they voiced astonishment at Peter’s advanced development and size as they compared him with their own young ones. What did I feed him? Did I have any outgrown baby clothes?

At one of our front yard meetings, Mary, a young resident of Furnace Quarters, asked me to come and see her sick baby, Booker, who had a hacking cough, a long-lasting bout with loose bowels, and was losing weight. I told her that she should take him to the doctor, but she refused. “He ain’t that bad and all that doctor will do is put him in the hospital, where I got to stay with him. I ain’t got nobody to keep my other young ones for me,” she said.

So I made that sojourn down the road to their world of misery and deprivation, which until then I had not suspected to exist in the shadow of the campus.

Furnace Quarters consisted of some twenty sagging two-room shacks strewn among the ruins of former coke ovens, which had long been abandoned. Two households occupied each two-room cabin. The floors were dirt. Crude fireplaces served as the only sources of heat and the only cooking facilities. Daylight came in through gaping, glassless, screenless holes that could be closed with crude wooden shutters. There was no electricity, and there were no indoor or outdoor toilet facilities. Open sewers collected the human waste, which in turn attracted flies and rats. One water faucet supplied the water for all residents. Mangy dogs and swarms of children played among piles of refuse.

The residents were mainly very young women, their children, and very old men. These were the forgotten poor who were excluded from the social services of the city and from white charity. They were the outcasts, whom the black middle class often looked upon as an embarrassment. No census taker counted them; no attendance officer checked on the children’s schooling; no health nurse or welfare worker gave assistance or advice; no bus transportation existed to help them get to town.

Every young mother has experienced the total absorption, exultation, love and pride that I felt at the miracle of development of our first child. He was the center of our thoughts and all the knowledge of baby care I possessed or could acquire was at his disposal. Through him my compassion for all children increased and with it an ardent desire to assist and protect them.

It was therefore almost inevitable that my emotions should be deeply aroused by the plight of the children of Furnace Quarters, whose mothers or caregivers lacked the means, the time, and education to provide their children with a healthful start. Peter’s good health caused me to become their “Doctor Lady,” as they called me. How impulsive and presumptuous I was then to assume such a role when I too had so much to learn! But at that time I responded without any doubts entering my mind.

On the following Saturday morning I went with Mary to her house, accompanied by some sociology students. We brought along a supply of baby foods, baby cereal, small cans of evaporated milk, boiled water, sterilized bottles, and some samples of Polyvisol, a baby vitamin. Booker was still coughing constantly and had a gray hue to his skin. He had never had any orange juice or vitamin supplement. His bottles were never sterilized, and his milk stood long in open cans before it was added to the unboiled tap water. We showed Mary how to give the baby five drops of vitamins daily, explained how to provide him with a safe milk supply, and left our gifts with her.

By Monday afternoon several women stopped by our house to ask me to come to their place to cure their babies with her wonder medicine. They told me that Booker got well by the next day. When I saw Mary again, she told me that she had given Booker the whole bottle of vitamins at once and it had cured him. I was lucky that this “better too much than too little” cure did not give the baby a case of vitamin poisoning. None of the women would believe me when I stated that Booker’s recovery was probably independent of her efforts.

The demand for me, the Doctor Lady, became so great that my student friends and I began making regular weekly rounds equipped with donations of vitamins and baby foods, a thermometer, a baby scale, a baby bathtub, and a supply of toys. After a few weeks we succeeded in getting the help of a black doctor to whom we could bring a really sick child. Mary organized our visitation schedule. She had risen to the prestigious role of coordinator.

At times we were forced to come up with unique methods of treatment. I remember seeing Ms. Ledbetter’s surviving premature twin two days after its birth and how we improvised an incubator for her out of a wooden box and hot water bottles wrapped in blankets. The baby survived. Ms. Ledbetter had given birth to the twins unaided, bitten off the umbilical cords, and cared for the babies and herself alone.

Another episode that stands our in my mind is that of a family who had status as healers and who talked against us because they saw them as competition. When a child broke out with severely blistered skin and we secured an ointment from our doctor friend, the local healer argued that she had a better treatment, namely the heating of an onion in fire and applying it to the blisters to burn them off. They had done this to their own child. When we asked how their child was now, they reported it was dead. There was no hesitation after that remark to apply the salve our friend Dr. Brothers had given us to the blisters.

The most tragic case we were called to assist with involved a serious fire in a locked cabin in which two children, two and four years old, had been left alone with a fire in the open hearth. The two-year-old fell off a chair headfirst into the fire. By the time the neighbors broke the door in, he was severely burned on his scalp and the upper part of his body.

Someone ran a half-mile to the nearest phone and summoned the fire department, which took the child to a doctor. A dressing was put on the burns to be replaced daily. However, several days of rain made it impossible for the child’s mother to return to the doctor. We were called when the child developed a high fever and the sores had festered. We rushed the child to the doctor, who made me hold him still while he tore the caked bandages off the child’s skin. I almost fainted. The child relieved himself of pain and terror with a steady barrage of wild curses. We then brought the child to the hospital where he was put naked into a bubble tent. Years later, some of the students raised the money to get skin grafts and plastic surgery for him so he could walk erect. No hair ever grew on his scalp.

Among the infant feeding practices I observed at Furnace Quarters, and also a short time later among sharecropper families in the Black Belt near Tuskegee, Alabama, were the pre-chewing of food by mothers, stilling hunger with sugar water, and calming fretful infants with a concoction of “assificidy” and whiskey, which put them right to sleep.

In the midst of all this squalor and decay lived one solitary man, Mr. G. W. Wilson, the newspaper peddler. He could be found any day at the southwest corner of the courthouse square sitting on a stack of the black newspapers he sold, reading the latest issue of the Congressional Record. He was Talladega’s only subscriber to this government publication and the most informed citizen regarding national politics and constitutional issues. In elections, however, he could not vote because he was black, poor, and powerless. The local voter’s registration board had failed him repeatedly in its examination for literacy. Passing this arbitrary examination and the payment of a poll tax were requirements for voting in the South during the first half of the twentieth century.

It was common knowledge in the black community that G.W. Wilson—christened George Washington Wilson—was the unacknowledged half-brother of Thomas Wilson, Esq., the powerful banker and president of the Chamber of Commerce. G.W. was raised by his mother on the Wilson plantation near town. As a young man he left to work in the mines near Birmingham. There he had become politically educated and fought for the right of black workers to join the union. Now, old and in broken health, but with his dignity and pride intact, he had returned to his hometown. G.W. never used his full name again so no white person could call him by his first name only, as was their practice when addressing blacks. Catering only to black customers, he had independence from whites. His economic needs were few, and he could easily afford to live in Furnace Quarters.

Mr. Wilson’s post on the corner of the square leading to the black residential section was a stopping place for many illiterate Talladegans who used his skill as a scribe and his knowledge as a reader of official government documents to get information on how to exercise the few legal rights they possessed.

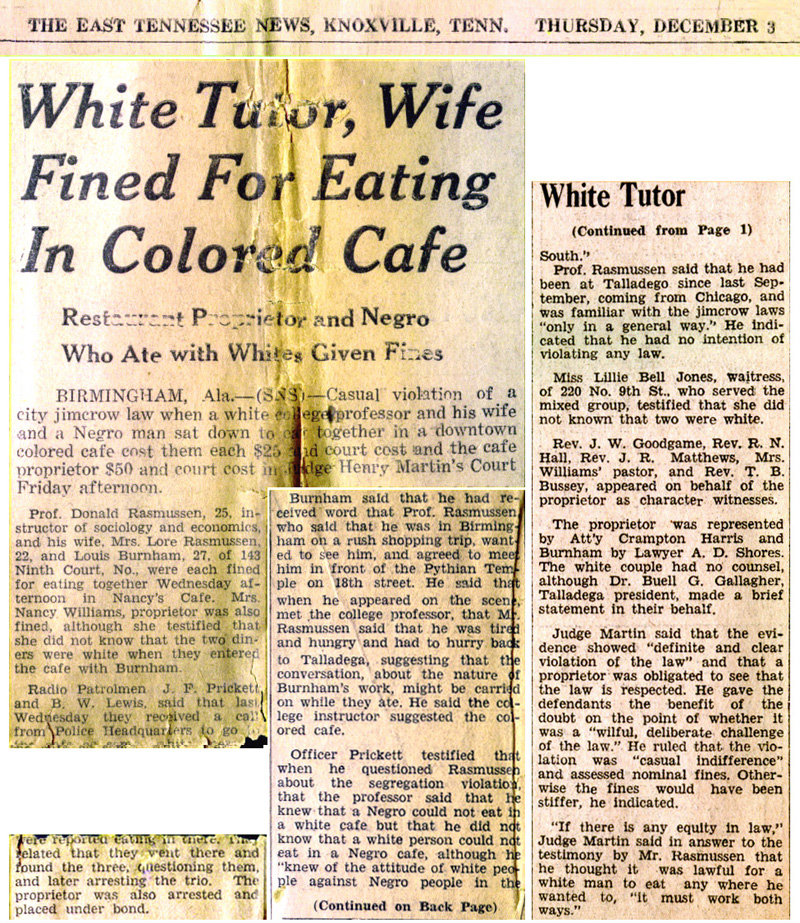

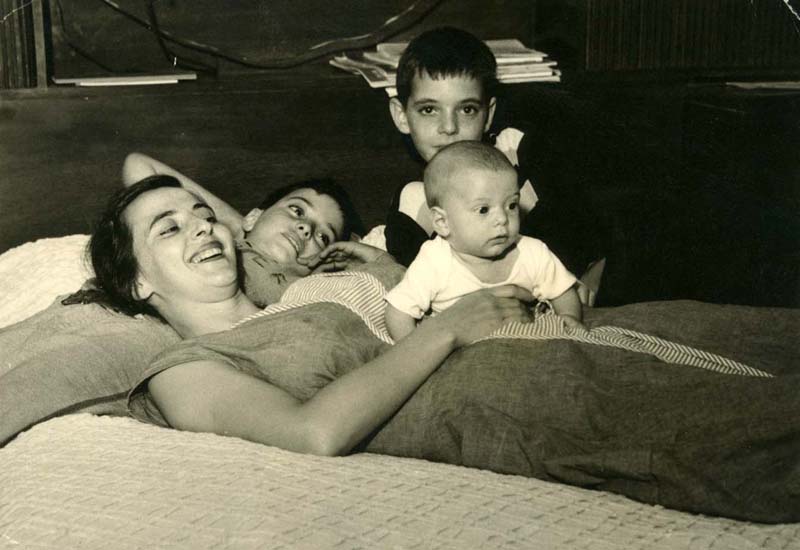

Lore, Don and Peter in 1946 in Schiller Park, Illinois.

I had served in the Army from 1944 until 1946. On our return to Talladega in the fall of 1946, Lore was fully occupied taking care of two boys and also helped me gather biographical data in Birmingham for my doctoral thesis on southern white liberals. We had found almost a hundred white people in Birmingham who qualified for our study and Lore interviewed about half of them. By the spring of 1948, we had completed gathering data and the boys were old enough to get along without Lore’s constant attention. After hiring some help to care for the house, Lore was able to accept an appointment as assistant professor of elementary education for the fall of 1948. Dean Cater had approached her about the position, and her contract was continued for the next three years.

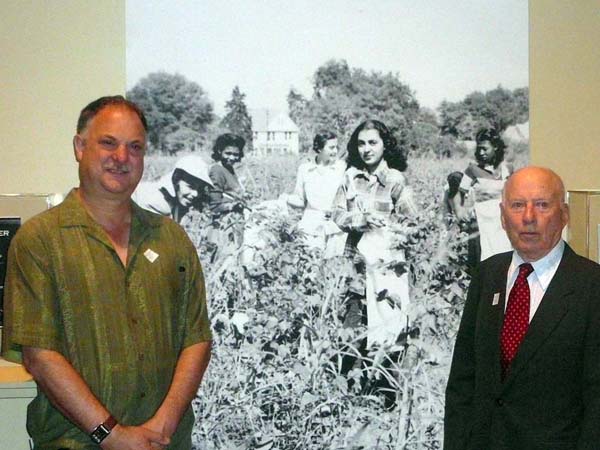

Lore was not one to follow an established pattern of doing things as they might have been done in the past. Textbook regurgitation was not her curriculum and lecturing to a class was not her style of teaching. Her students delved into the surrounding community, even into the cotton fields, which at that time occupied land adjoining the college. Why have teacher education in a cotton field, of all places? Some schools in Talladega County were still closed in the fall of the year so that children might spend their days in the cotton fields adding their bit to the family income. It was not enough to read about child labor, according to Lore, if there was the opportunity to go into a field and feel the backbreaking labor of plucking cotton balls from each plant and dragging a heavy bag down each row.

On some occasions, Lore took children along with her student teachers on field trips—an unheard of practice—to have first-hand experiences in nature study, environmental education, and collecting raw materials for art projects. On one such trip, Lore says, “I learned from the children how to smoke a ‘possum’ out of a tree.” And her students interviewed elderly people in the community to get firsthand accounts of the recent history of the community, including a lynching and its aftermath.

Lore also found a collaborator in Mr. Miller, head of the college’s maintenance department. Her students wrote plays for children, and then made marionettes in Mr. Miller’s workshop to put on puppet shows. They learned practical science from Mr. Miller, who “let us take a lawnmower apart and put it back together again to see how a gasoline engine worked.” Her students kept journals about butterflies and moths they hatched from cocoons and about the silkworms they raised on locally grown mulberries. She turned her classroom into a science lab that addressed fears, superstitions, and taught how to teach children science without a budget for supplies or textbooks.

Lore supervised students who were doing their practice teaching at the all-black Westside Elementary School, which had few supplies, few textbooks, and crowded classrooms. She recalls, “as a white teacher I was ‘breaking the law’ for even supervising the students. Once Mrs. Isbell, the classroom teacher whom my students worked with, hid me for a whole day in the dark utility closet when the white county supervisor came to inspect the school.”

All Lore’s students traveled to New York with her to visit some of the outstanding elementary schools of the country. Arrangements were made for them to practice teach at the Little Red Schoolhouse, the City and Country School, and the Ethical Culture School in New York, at the Laboratory School of the University of Chicago, and at other progressive schools. These experiences helped Lore’s students become conscious of the needs of their future pupils. Such learning contrasted with students’ other experiences in the local segregated Talladega public schools.

Of course, such a program raised questions within the college administration. Dean Cater was thrilled with the enthusiasm of elementary education majors who had had the reputation of being students who would fail to make the grade in other departments of study. Now many more students had an awakened interest in elementary education. President Beittel, however, had another view which he voiced to Lore: “What could students who were going to teach in the Deep South learn of practical value from traveling all the way to New York to observe and work in classrooms they would never see the likes of in their future positions in the segregated South?”

Lore (rear) and her students on a field trip picking cotton.

Lore wrote this story as a thirteenth birthday gift

to her grandchildren Rochelle and Meril in 1987.

Today’s true story happened about forty years ago. It is about seemingly simple people and nothing very dramatic happens. No one goes to jail this time and no one gets hurt. But after forty years the details are as clear in my mind as if they had happened yesterday. I wonder if you will be able to tell me why when you have finished reading this.

World War II was over. The Germans were defeated. Grandpa had been discharged from the army and our little family had just returned to Talladega College in Talladega, Alabama, to the same little house on the campus where we had lived three years before.

One day in February 1948, our doorbell rang and an unfamiliar, neatly dressed and kindly looking, brown-skinned man in his early forties was at the door asking to speak with me. He introduced himself as Zebedee Christian, a janitor at the Alabama Institute for the White Blind. He had heard that I knew German and he wondered if I would translate a letter that he had just received from Germany. I agreed and invited him in. Here is the letter:

Oberligen, Germany Jan. 10, 1948

Very Honored Mr. Christian;

Ladies and Gentlemen of the Assembly of God;

Dear unknown benefactors in America:

Just before Christmas, representatives of an American relief group met at our church and handed out gifts from the American people to households of women and children. My daughter and I were given your generous holiday food package. In it we found your name and address, so we rush to thank you. It was the first time that we had coffee, tea, and sugar since the war began. It brightened our otherwise bleak holiday. How lucky you are to have been spared the suffering of war in your land and not to know hunger.

We are sending you this picture of the two of us. On the back of it I wrote the sizes of the clothes we wear. We are very much in need of warm things. My daughter and I both need raincoats and rubber boots and I could use several pairs of nylon stockings.

May God bless you for your charity towards two helpless women who once knew better times.

Please send us a picture of you. We will keep it in an honored place.

In eternal gratitude and with highest respect,

Mrs. Lisa von Platten and daughter Elsa

Mr. Christian shook his head in amazement as he listened to the contents of the letter. Then he asked me to read the salutation again. His face lit up with an amused smile as he said: “White folks around here don’t even call me ‘Mister’ and she writes about me as if I were a white judge!”

My own feelings were in utter turmoil.

I was deeply touched by the pleasure Mr. Christian derived from this letter. I knew how respect and manhood were denied him by his own society, and yet he himself had the compassion to reach across the ocean to aid strangers. To him this letter of thanks was a gift of dignity received and of far greater value than the gift he sent.

But I was very angry with Lisa von Platten and the society she represented. She could have been among the Nazi hordes that had murdered most of my family. Her “von” in her name and the better times she alluded to indicate aristocratic origin.

Yet how could Lisa von Platten know who would receive her letter? She could not know that members of Mr. Christian’s family and his friends had never owned raincoats and nylon stockings and in all probability never would.

Should I tell Mr. Christian about my own persecution by the Germans, tell him that those who survived the war have a better material life ahead of themselves than he has? I chose not to interfere with Mr. Christian’s joy and wonder. Instead I asked Mr. Christian to tell me about The Assembly of God.

We of The Assembly of God are a small group of families who left the African Baptist church and decided to set up our own Christian ministry without a preacher. We select from the Bible those passages that speak of doing God’s work by helping our fellow men. We think of God as a loving father who wants his children to live a brotherly life. We think worship is doing good deeds. Prayer alone is not worth God’s attention. God does not want to rule by fear. God does not want us to suffer passively and wait for our just reward in heaven and wait for the sinners to be punished in hell. God wants us to work now to make this life better. That is our religion.

You can find all this written in the Bible, but you have to look hard to find it. We observe the Lord’s Sabbath by putting on our work clothes and donating the labor of our hands as a group to help someone who can’t manage alone. We don’t do it for them but do it with them. We tax ourselves by giving up one-tenth of all our earnings to the assembly. This is called a tithe. It gives us the money to buy the materials and tools to do our projects with.

I invite you and your husband to come with me to our assembly next Sunday. You can then read the letter to all of us and see what we do.

The following Sunday Zebedee Christian was again at our door. This time he was dressed in a pair of coveralls. We climbed into our car and drove from the west side of Talladega, where the stately tree-shaded campus with its imposing Greek Revival architecture was located, to the far east side where poor black people lived in scattered cabins. We left the car when the dirt road became impassable and proceeded by foot up a red clay bank. From there, a footpath led through a cotton field to a small gray cinderblock structure, which we entered.

Inside, in the semi dark, we found a group of people sitting on wooden apple crates conversing quietly. Mr. Christian introduced us to his assembled friends and explained why he had brought us. They were: Willie Brown, a shoemaker; Sadie Jones, a maid; Elizah Wilson, a peddler; and Isaiah Long, a blind broom maker.

This is where we meet every Sunday morning. We built this one-room house for Isaiah to live in and to use as a workshop where he teaches other blind men how to make brooms. Isaiah learned broom making and chair caning up north in a training school. Here we have no training school for the colored blind, so they are a burden to their families. I saw a workshop and a store at the white school, and we decided to start one of our own in the Lord’s name. Our families take turns doing chores for the men, and my oldest son goes around town to sell the brooms. Our next job is to build a pigpen and a fence, dig a little garden for greens, and get a few chickens and a pig.

After this explanation the short formal meeting began with a scripture reading and a report for the group on their efforts during the previous week. At the end of each person’s statement they revealed the week’s personal income and deposited a tenth of it in the common collection box. The maid could not make her contribution because she was still owed her five dollars pay, and the shoemaker had not had much work during the previous week and could only pay two dollars. Isaiah had sold three brooms and contributed thirty-five cents.

Then I was asked to read the letter from Germany. Again it was received with pleased astonishment and pride. After some discussion, it was decided that they would not send a picture: “If the ladies see we are colored, they might not feel so good about getting our help.” There was immediate consensus, however, that a clothing package should be sent when they could get the money together.

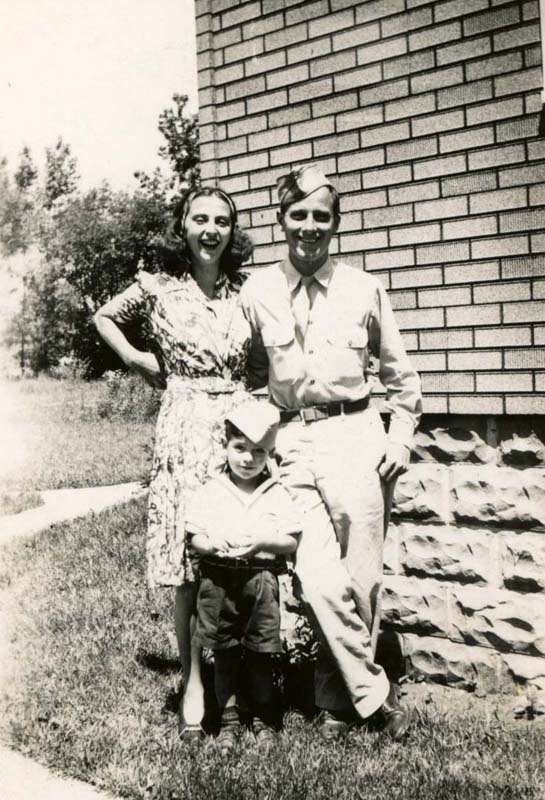

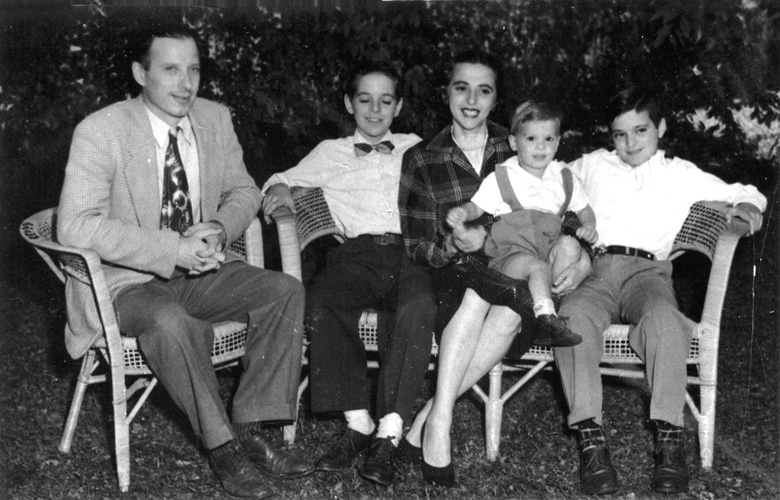

Lore and Don with their sons Peter (right) and David, around 1949.

Lore wrote this story in 1987 for her grandson Michael’s eleventh birthday.

In 1950, if you wanted to go from Alabama to New York as a white teacher with your black students, there was more to train travel than having the money to buy tickets. This I found out.

I was an assistant professor of elementary education at Talladega College and had received a travel grant that permitted me to take seven black students to visit the best progressive elementary schools in New York City. The purpose of the trip was to expose my students to creative ways of teaching and learning to serve as an antidote to the drill-centered, inadequately supplied, segregated Alabama schools in which my students were forced to do their student teaching. Parents of the schools had invited us to be their houseguests during our New York stay. It would be the first time that most of the students had set foot in the North, and certainly the first time that they would be living with white families. Many cultural and educational experiences had been planned for us. If the trip had its intended outcome, several of the students would be able to do part of their student teaching in the schools selected and would live with the same families. Little did we realize that getting to New York would be the most memorable part of the trip.

At that time there were two railroad lines, the Southern Railway and the Seaboard Railroad, which had accessible routes to New York. We first went to Anniston to book seats on the Southern Railway. Approaching the ticket window in a racially mixed group, we were assigned to racially segregated cars. I was to sit in a white coach and my students were to sit in a coach reserved for blacks. We were told that on the return trip, which originated in New York, we could sit together. We refused to be separated and pointed out the economic loss to the company caused not only by the non-purchase of our tickets but by the boycott of the railroad we planned to initiate on black college campuses. The local agent, who knew that Talladega students might make good on their threat, reversed his original decision after checking with his Birmingham office. However the Washington headquarters of the company insisted on segregated seating, and the local southern agent apologetically returned our money a few days later.

Fired up with righteous indignation and feeling buoyed by the negotiating power the price of eight tickets gave us, we proceeded to the Birmingham office of the competing Seaboard Railroad. We told the agent that we had been refused unsegregated seats by Southern and that not only would we purchase our tickets from them if we could sit together, but we would also make that fact known to student chapters of the NAACP and to black fraternities and sororities. The agent disappeared to contact his company’s headquarters in New Orleans and returned to tell us that he was authorized to sell us unsegregated tickets. We were jubilant with our victory.

On our departure date we drove to Wellington, a railroad flag stop near Anniston, to await the arrival of the New Orleans to New York Express, which would make a special stop to pick us up. We could see many heads looking out the windows and many porters and waiters congregated in the areas between the cars. A conductor came to meet us, took us to the last coach, and helped us in with our luggage. There were many bemused and puzzled expressions on the faces of the watching train personnel for which we had then no explanation.

The car we entered was a private railroad car—half lounge, half Pullman sleeper. As we learned later, it had been attached to the train in New Orleans for our exclusive use. None of the train crew had any idea who the important passengers were for whom it had been reserved. All they knew was that it would be occupied at the Wellington flag stop. Speculation among the personnel ranged from top railroad officials on an inspection tour to high government dignitaries or foreign diplomats. No one was psychologically prepared for eight young women, seven black and one white! Needless to say, we were as surprised as they were to find out the degree of ingenuity the railroad had employed to serve us according to our wishes, hide their making an exception to existing segregation practices, while at the same time gaining a considerable public relations advantage over the Southern Railway.

We had our own porter assigned to us. He was black. (All Pullman porters and dining car waiters on American trains were black, just as all engineers, conductors and dining car stewards were white.) He greeted us with laughter and disbelief and wanted to know who we were and what we had done to get this extraordinary treatment. At the end of our story he excused himself so he could repeat it to his black colleagues who were waiting for news from him.

With delight, we examined our quarters in some detail. There were comfortable armchairs, tables with fresh flowers, magazines, and playing cards. The walls were covered with wood paneling. Small wall lamps lit up the spaces between the curtained windows. Our beds were already made up in the other section. We felt we were on a Hollywood movie set, but the train was moving and we were on our way to New York!

Within minutes a waiter appeared with a pitcher of iced orange juice to quench our thirst, serving us with a twinkle in his eyes and saying “with compliments of the Seaboard Railroad.” An hour later he returned with printed menus from which we were to select our dinners, which arrived with champagne and were served on tables with white tablecloths. Again he repeated his announcement, “with compliments of the Seaboard Railroad.”

Before the evening had ended we had also been treated to mints and pralines. A constant stream of black porters and waiters visited us and shared with us their great delight in the absurd and costly consequences to the railroad of our refusal to be separated. They confirmed what by now we suspected. The railroad officials had left detailed instructions on how to hide us completely from other passengers by anticipating our desires so we would have no need to go to the dining car and challenge the segregated seating in that section.

By the time we reached New York, we had discussed among ourselves and with our visitors the potential power of black boycotts to bring about change. Five years later this was dramatically proven in Montgomery, Alabama, when Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus, and the subsequent bus boycott by black people led to the abolishment of segregated seating in public conveyances.

Whatever serious analysis one can make of our deluxe travel at coach prices, we loved every minute of it. It will be the only time in our lives where we will ever travel in a private railroad car “with compliments of the Seaboard Railroad” or that of any other common carrier.

Lore with David, Peter and Stevie in 1952.

Grandma Myrtle, Stevie, Erna, Don, Lore. Tom, David, Peter and Flash in 1952.

Lore with Don, Peter, Stevie and David in 1953.

* * *

In February 2001, Lore's experiences at Talladega College were included in the PBS documentory From Swastika to Jim Crow. The show recounted the experiences of a handful of Jewish refugee scholars who found new lives and careers teaching at historically black colleges and universities in the South.

See Lore in the preview of From Swastika to Jim Crow.

Read the synopsis of From Swastika to Jim Crow.

Read a review of From Swastika to Jim Crow.

Order a DVD of From Swastika to Jim Crow.

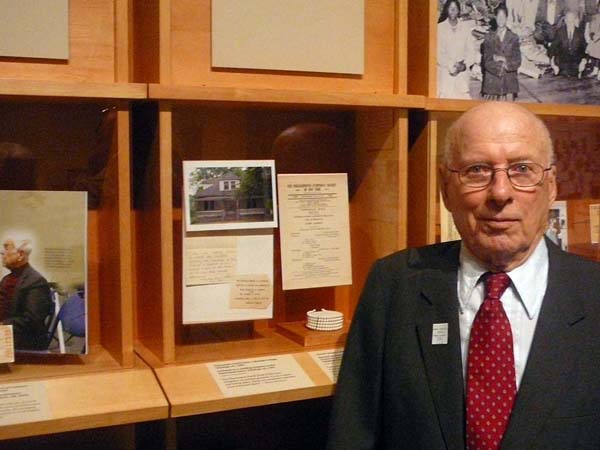

On May 1, 2009, the exhibition of Beyond Swastika and Jim Crow: Jewish Refugee Scholars at Black Colleges opened at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City. The exhibition a section about Lore's experiences teaching at Talladega and will run until January 4, 2010.

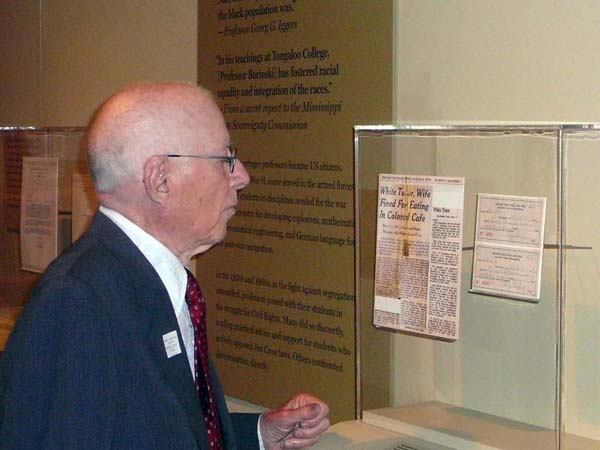

Don and Steve visited Beyond Swastika and Jim Crow on June 23, 2009.

Lore (center) is picking cotton with her Talladega College elementary education students,

who may soon be teaching in rural Alabama schools.

Don stands next to a photo of the Rasmussen house at Talladega College.

Don reads a 1942 newspaper article about his and Lore's arrest for eating in a restaurant with a black friend in Birmingham, Alabama. On the right are the receipts for the fines he and Lore had to pay.